Revolution Blues and the American Psyche

“But I’m still not happy / I feel like there’s something wrong.”

Neil Young’s “Revolution Blues” stands as one of the most controversial and powerful songs in the rock canon. Originally recorded for 1974’s “On the Beach” – the middle chapter of Young’s legendary “ditch trilogy” – the song emerged from one of the darkest periods in both Young’s personal life and American cultural history.

Written in the shadow of the Manson murders and during Young’s own struggles with fame, addiction, and the deaths of close friends, “Revolution Blues” channels the paranoid energy of the early 1970s. Young had briefly encountered Charles Manson in Topanga Canyon months before the Tate-LaBianca murders, the Kent State shooting of student protestors still hung in the air, and I wonder if it felt like the overly sweet 60’s had turned sour after the assassinations of ‘68 and ongoing war waged against Vietnam.

This song gives voice to the mad people – paranoid and isolated individuals whose ramblings seem like just part of the mix in the upheaval of late 60s California. In this case, Charles Manson, who cultivated a family of brutal murderers steeped in apocalyptic mythology. Would that this type of behavior was bygone memory.

The whole album is chock full of an incredibly heavy sense of grief, channeled through the art form of slightly odd rock music. You can hear the world and time bend on this album, and the only way to capture that—as everyone knows—is to record while it’s happening. Part of that time warp was, evidently, a chance to look into the future at a trend that has come front and center. Many of us labor and wait, for we are not yet at the high water mark of the scary clowns currently making violence. Such as these express anxiety as deep and old as America itself.

With our history? I would be anxious, too.

From Salem witch trials to McCarthyism to QAnon—the genocidal rampage against the complex indigenous first nations, and the profound unease of held chattel captives outnumbering captors—America has always expressed a tendency to feel victimized by invisible oppressors while creating very real scapegoats and victims in a self-fulfilling prophecy. This cycle of paranoid fear and retaliatory violence forms part of our cultural memory, passed down through generations.

One way to address this cultural trauma is the route Neil Young took here, with Revolution Blues. By embodying the menacing aspects of a suspicious world, we join on a journey into the mind of darkness. I wonder if the association between music and remediation, much older than our modern anxieties, might offer us a balm for these social ills.

The “On the Beach” version featured David Crosby on rhythm guitar and Levon Helm and Rick Danko from The Band. The contrast between the song’s funky, almost danceable rhythm and its apocalyptic lyrics creates a tension that captures the era’s cultural upheaval. The whole band was heavily medicated on strong edible cannabis through the recording process. This dark period followed multiple personal tragedies, including long-time friend and guitarist with Young, Danny Whitten’s, fatal heroin overdose.

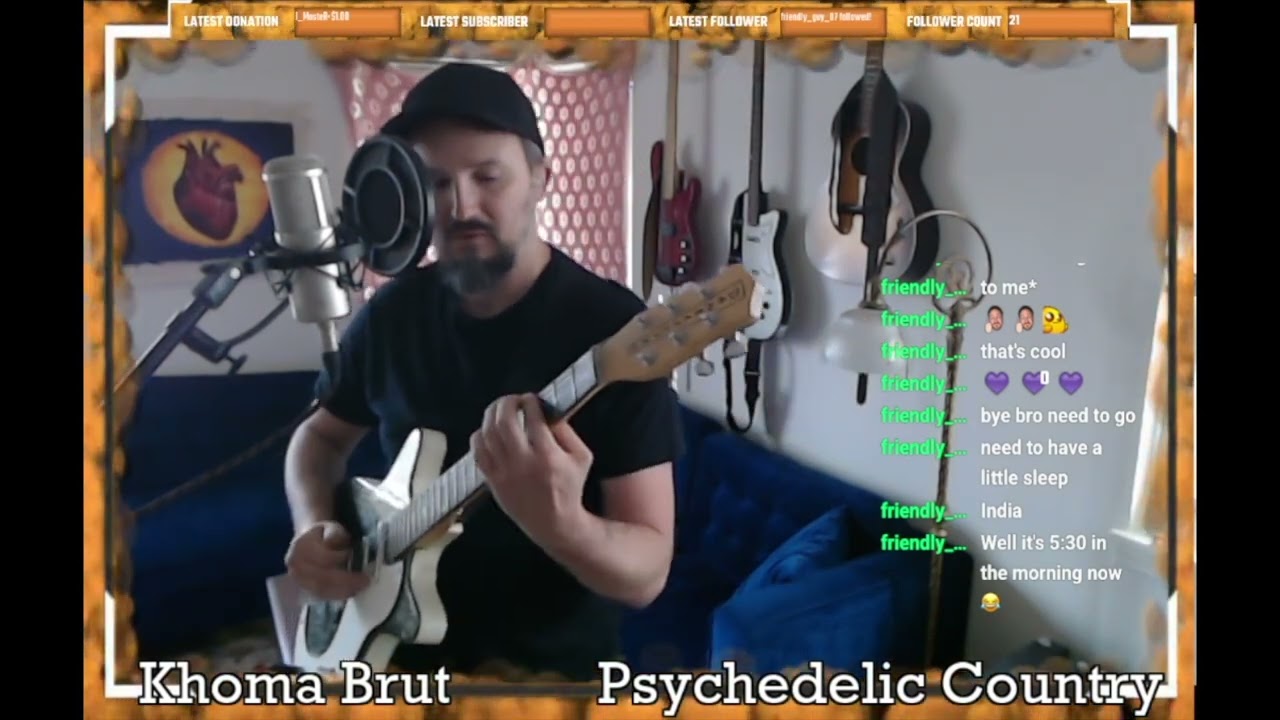

I love performing “Revolution Blues” because it has such a heavy lyrical presence, but the drive of the original has become, for me, slightly more composed. I open with this syncopated lyrical passage inspired by the original, which then tightens up through the sung passages.

One thing to look out for: the change into the IV minor 7 chord—the one at the lyrics “revolution blues, bloody fountains.” That’s quite a beautiful and sweet transition, especially compared to the startling lyrics.

This combination of very heavy and very beautiful is the classic move common with psychedelics and altered states: mix the putrid with the sweet, violence with gorgeous images, because therein the magic lies. This song artfully names a tension as old as America, and in so doing helps to grieve and address those injustices.